THE DEATH OF BOBBIE KOLADA, Part 3: ‘I remember thinking I was going to die’

Published 5:30 am Thursday, May 25, 2023

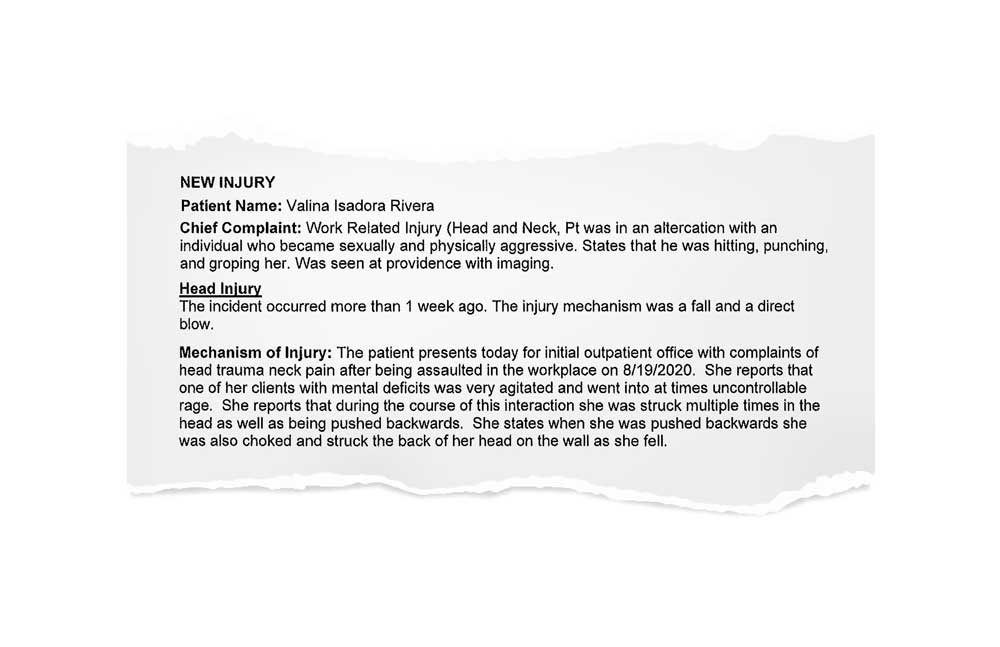

- Scan 2 Caregiver NEW

EDITOR’S NOTE: Part 3 of a five-part series.

Trending

******

When Jacksonville resident Valina Rivera-Schaefer learned that caregiver Bobbie Kolada had died in March as a result of an apparent attack by a resident at a Medford group home for developmentally disabled adults, she could hardly catch her breath.

The news brought a tidal wave of dark memories for the 35-year-old, from a painful miscarriage after one of many violent attacks she endured as a caregiver to a slew of on-the-job injuries and recurring nightmares about conditions in which she and others like Kolada worked.

Trending

Some of the injuries Rivera-Schaefer suffered occurred at the same house where Kolada was fatally injured, while others happened at different homes.

Kolada and Rivera-Schaefer both worked for Partnerships in Community Living, a Monmouth-based nonprofit that operates the group home in east Medford where Kolada was injured, as well as others around the state.

Kolada was critically injured Feb. 20 by a man for whom she provided care. She suffered several crushed vertebrae and a serious head injury, from which she never recovered.

“She grabbed the remote out of my hand and started beating me in the face with it and chasing me around the house. I’m bleeding and crying, and she wouldn’t stop. No help was coming. … I remember thinking I was going to die.”

— Valina Rivera-Schaefer, former PCL caregiver

After learning that Kolada died March 27 after five weeks in the intensive care unit at Rogue Regional Medical Center, the Rogue Valley Times reached out to past and present employees of PCL about their experiences in the company’s group homes. Several said work-related injuries — ranging from bites to concussions and dislocated limbs — are common.

Employees said they work long hours, even double shifts, in stressful, understaffed situations and are often left alone with residents whose behaviors call for restraint measures requiring two trained staff members to administer.

Still struggling with health issues from her time at PCL, Rivera-Schaefer remembers going to work despite fearing she might not come home to her family.

Getting hurt at work became the norm

Hired in January 2021 to work as a house manager and occasional caregiver, Rivera-Schaefer said she was sent into her first group home — a home for developmentally disabled minors on Canyon Avenue in east Medford — before her training was complete.

“Three days into training, they were like, ‘How would you feel about going into a house? We’re short-handed.’ … They didn’t introduce me to the individual or let me go to the house first. They were just like, ‘We need someone now. It has to be tonight.’ I was like, ‘Uh, OK, I’ll try it out,’” she recalled.

“It was supposed to be overnight. They said the residents would be asleep already and, if they wake up, you just turn on the television. They always would try to sell you on, basically, how you’d be ‘all set’ for the night. They tell you people are close by, that you have an on-call available if you need help. … But you literally have no idea what you’re walking into.”

To mitigate challenging or dangerous situations in residential settings, caregivers receive mandatory training under the Oregon Intervention System, which outlines de-escalation techniques ranging from calming tactics to restraint, some of which require two people to administer.

But Rivera-Schaefer said caregivers almost always worked alone, regardless of an individual’s known behaviors.

“Two o’clock a.m. rolls around, and this girl comes out, she’s banging on the door. I’m doing everything I can to de-escalate her. I’m giving her a snack and trying the other things it says in her plan,” she said of her first night in the house.

“I called the person who was on call. I said, ‘She’s becoming escalated. She said, ‘Just go turn on the television.’ And I try to joke around about this, but it was awful. They didn’t tell me how to turn on the satellite — or that it hadn’t been working for a couple days. So, I’m trying to find her show, and it just made her madder. I couldn’t get Mickey Mouse. I couldn’t get cartoons. All that would come on was Reba. And she … did not like Reba,’ Rivera-Schaefer recalled.

“She grabbed the remote out of my hand and started beating me in the face with it and chasing me around the house. I’m bleeding and crying, and she wouldn’t stop. No help was coming. Two hours of being assaulted, and the entire time I’m making calls to the on-call, begging for somebody to help me. … I remember thinking I was going to die.”

“I was on a computer doing a Zoom meeting with people from Portland and Eugene, and they were like, ‘What’s going on?’ They could hear him in the background yelling, ‘I’m gonna f–k her, I’m gonna kill her, I’m gonna f–k her, I’m gonna kill her!’”

— Valina Rivera-Schaefer, former PCL caregiver

After two hours of being kicked and “thrown around” — Rivera-Schaefer later filed an injury claim for a head injury, broken teeth, dislocated jaw and a hip injury — an on-call employee finally called back, just as Rivera was ready to call 911.

“She said, ‘Do not call 911. You don’t need to call 911. You don’t need to be dramatic about it.’

“The next day there’s a team meeting on video, and they made me get on this meeting, literally the day after I got my a– beat. All these people were like, ‘Wow, we heard what happened and you’re back here today? You’re a trooper.’ I felt like I’d survived something crazy. They were building me up. I felt like Rocky.”

Still dealing with a head injury — and despite doctors ordering light duty — she said PCL sent her back to the house with “the girl who didn’t like Reba,” as well as others. Getting hurt at work became the norm, she said.

When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemonade

A 17-year-old resident at a PCL group home for developmentally disabled minors on Edwina Avenue in Central Point was the second client to send Rivera-Schaefer to the hospital.

“I’m three or four months pregnant, and one night he’s escalating because he wants chicken nuggets and “Finding Nemo” at 3 a.m. I’m telling him no and trying to calm him down, so he’s kicking me in the shins and in the abdomen. He got a running start and kicks me directly in the knee, and I swear he almost broke my kneecap. I go to the hospital and I’m spotting (bleeding), worried I’m about to lose the baby,” she said, fighting back tears.

Before she went to the hospital, Rivera-Schaefer said, a PCL employee asked her to sign a release of liability.

“The next day, I lost the baby,” she said. “We had to schedule a (dilation and curettage) because I couldn’t pass everything on my own. As I was going into surgery, I got a phone call from my boss asking when I would be back at work.”

Rivera-Schaefer said PCL responded to her miscarriage by giving her $1,000 and a lemon-themed gift basket with a tag that read, “When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemonade.” She remembers telling co-workers what had happened, including Kolada, who cried with her over the loss of her unborn son.

After being denied Workers’ Compensation following the miscarriage, Rivera-Schaefer was assigned to a PCL house on Bristol Road where, she said, she was punched, choked and sexually assaulted by a resident known to escalate on female caregivers.

“He escalated every day I worked with him, but they wouldn’t let me out of this house. It was like being trapped inside a horror movie,” she said.

Rivera-Schaefer said the male client’s behaviors were predatory, including habitual masturbating as well as ripping clothing from, and cornering and choking, caregivers. He once threw her to the ground and sat on her while ejaculating. During another incident, she said, the man “almost broke my neck.”

“He would sit outside my room, throwing things at the door. He threw hot coffee on me. He would clog toilets so I’d have to come out of the office. He’d take off his clothes because he knew that was a way that I’d have to touch him, to get his clothes back on. He would scratch out the poop from his behind and eat it and then try to scratch you with his nails,” she said.

“I was on a computer doing a Zoom meeting with people from Portland and Eugene, and they were like, ‘What’s going on?’ They could hear him in the background yelling, ‘I’m gonna f–k her, I’m gonna kill her, I’m gonna f–k her, I’m gonna kill her!’”

She was really devoted to the job

Rivera-Schaefer’s husband, Jeremy Schaefer-Rivera, who went to work for PCL in May 2021, remembers an overwhelming sense of dread when his wife left for work. Schaefer-Rivera said he was attacked, as well, including one resident who bit him hard enough to nearly tear a vein from his arm.

“Whenever you would get hurt, PCL’s only focus was how they needed you to get back in there. They play mind games with you and say, ‘These people need you.’ A person who is violent and can’t get in trouble for hurting or killing someone, and you’re the only one who can help them,” he said.

“Valina was at a house with (a resident) who lived alone because he beat all his housemates so badly he had his own house. I requested to go cover her, to be support staff, so I could keep her safe. The director told me they would take care of it. It felt like they wanted me to put the job over my own family. … And their idea of backup was they told her to put a chair under the doorknob to keep him inside. She was trying to do laundry, and he came out and was choking her and pushing her over the washing machine, punching her in the face.”

“The kid that kicked our baby out of my wife was supposed to have two people at all times, and he didn’t even have a half a person. A lot of times there would be four kids in a house with one, maybe two, (staff),” he said.

“There needs to be change. People need to be protected when they do this job. There needs to be justice for Bobbie. Valina warned PCL years before this happened that it was not safe. She warned them that somebody was going to be severely injured or killed.”

Schaefer-Rivera choked up when he learned of Kolada’s death.

“She was a great woman who just wanted to take care of her boys. Bobbie worked 9-to-7 when I worked 8-to-5. I had a lot of interactions with her,” he said.

“She was really devoted to the job. I still have her number saved in my phone under ‘PCL Bobbie.’”

Coming Wednesday — Part 4: Caregivers describe “culture of allowing abuse”

Part 1: ‘Did somebody do this to her?’

Part 2: Who is investigating Bobbie Kolada’s death?

Part 3: ‘I remember thinking I was going to die’

Part 4: ‘Culture of disregard for employees’

Part 5: ‘I don’t want her to have died in vain’