OUR VIEW: How we value the Greenway depends upon what first we see

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 12, 2023

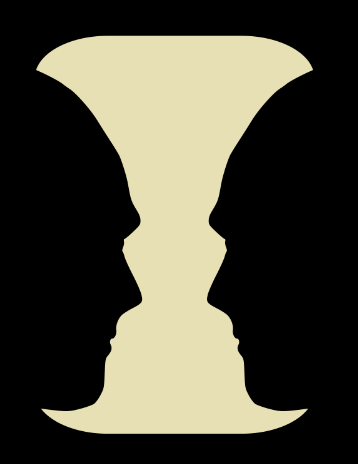

- Rubin's vase: What do you see first?

Rubin’s Vase is a famed optical illusion that has something to say about the way we view the Bear Creek Greenway.

The illusion, developed in 1915 by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin, is a graphic depiction of a vase — with the empty space surrounding it revealing itself to be a pair of faces in profile looking at each other.

Or … it’s the graphic depiction of two faces in profile, with the empty space between them revealing itself to be a vase.

Which is seen first mostly depends on who is doing the looking.

So it is with the Greenway — which for many, especially in Medford, has become something of a four-letter word.

If you focus your vision on the roughly three-mile stretch through the city, you see an area that justly has earned a reputation as an unclean and unsafe area. Chronic drug use, violent acts, harassment of Greenway users, trash-filled areas where campsites have proliferated — all of these have contributed to a negative perception of a trail meant to extol the environmental virtues of living in Jackson County.

But look at the surrounding spaces, the 17 or so miles on either side of the Medford stretch, and it’s easy to see what the Greenway was meant to be. Bike riders, joggers, those out for a stroll enjoying the freedom of vehicle-free paths and taking advantage of connections to city parks and local businesses.

“I always get a little bit nervous,” Steve Lambert, Jackson County Roads and Parks Department director, admitted while giving a recent tour, “when folks think of the entire Greenway as ‘that Medford experience.’”

It has been over a decade since the Greenway was completed from Ashland to Central Point, and while city and county officials would hope that it becomes known for its aesthetic beauty and as a transportation corridor, the stigma has dominated the discussion.

Efforts are being made to, if not erase that view, at least improve upon “that Medford experience.”

City Council’s recent decision to create a 500-foot non-camping zone in public areas has begun to have an effect along the troubled stretch. Increased public awareness of such attempts to improve security and sanitation also can play a part alleviating the image.

“Our goal is for people to start seeing the Greenway as an asset and not a problem,” Lambert said. “Getting people out to actually experience it is a big part of that shift in thinking.”

More, obviously, needs to be done. The Greenway’s issues are joined at the hip to those surrounding issues of drug use and homelessness. It took the collaboration of the public, individual cities and the county itself to bring the trail to life; it will take such collaboration to make it whole again.

Until that time comes, changing public perception of the Greenway — from a danger zone that has wrecked its overall reputation, to something of great value marred by its most troubled stretch — reminds us how much there is to gain.