GARDEN PLOTS: With patience and seeds, you can grow a native wildflower garden

Published 6:00 am Wednesday, November 15, 2023

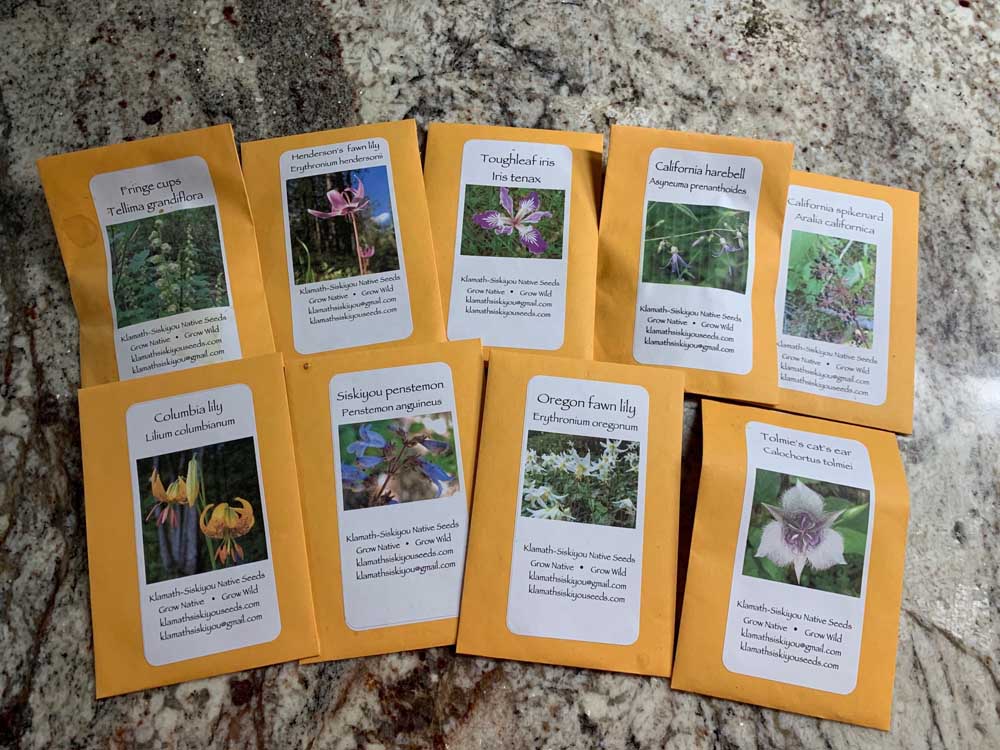

- The author has several packets of native plant seeds that can be sown in the fall: broadcasted in a prepared, weedless planting area; sown in pots or trays and placed outdoors to overwinter; or placed in the refrigerator until cold/moist stratification requirements are met.

“Since I have many squill plants in my garden, I am often asked where they came from. The answer — one that surprises those who ask — is that I sowed most of them myself, but some were salvaged when a ditch was being dug for a sewage pipe, and others by the roadside.”

Trending

— Meir Shalev, “My Wild Garden: Notes from a Writer’s Eden,” 2020

Meir Shalev begins his garden memoir with a story about shooing off a bride and groom, their mothers, and two wedding photographers from his garden in Israel’s Jezreel Valley. When he told the group they were trampling his flowers, the mothers ignored him, one asking the other, “Does this look like a garden to you?” and the other responding, “No, it looks to me like the countryside.”

The only way Shalev could get the party off his property was to tell them his automatic sprinklers would turn on in three minutes “and then you’ll see whether this is countryside or garden.” The group beat a hasty retreat.

Trending

Shalev doesn’t have sprinklers in his garden, and he admits his field of wildflowers is “neither neatly organized nor well kept.” Nonetheless he is devoted to planting a variety of native and naturalized plants that he procures from neighbors’ gardens (with their permission), local plant nurseries or along roadsides.

He rescued his first planting of sea squills (Urginea maritima), known as hatzav in Hebrew, after he happened upon a road crew excavating large clusters of the bulbous perennial, which are members of the asparagus family. However, Shalev says, “The squills I love the most are those I sow myself and for whom I wait patiently to bloom.”

In fact, it takes 10 years for the first squill blossom to appear in late summer when most other plants are lying dormant in defense against the brutal Mediterranean heat. Yet sea squills have adapted to the hot, dry climate by producing leaves in the spring that enable the underground bulb to store food. The waxy flowers are produced from thick, fleshy stalks; the plant is also poisonous to discourage predators.

The other wildflower mainstay in Shalev’s garden is winter-blooming cyclamen (C. hederifolium and C. coum). Like many of the squills, Shalev grows most of his cyclamen from seeds, which produce their first flower after three or four years. Not only do the flowering cyclamen readily self-seed, but their corms continue to grow throughout their lifespan, adding more leaves and flowers over the years.

Interestingly, unlike other Oregon cities, Medford has a Mediterranean-like climate. Our hot summers and wet, relatively mild winters are similar to, if not as extreme, as the region where Shalev gardens in Israel. Whereas the USDA hardiness zones in the Jezreel Valley are 10a and 10b, Medford’s hardiness zones are now designated as 8a and 8b (an increase from 7a and 7b when I moved to the Rogue Valley twelve years ago).

Like Shalev and many other gardeners these days, I’m interested in adding more biodiversity to my garden, and an effective way to do that is to add more native wildflowers. I recently participated in an OSU Extension Service program “Growing Native Plants from Seed,” during which Suzie Savoie, co-owner of Siskiyou Ecological Services and Klamath-Siskiyou Native Seeds, shared her extensive knowledge of native plants in our region. Here a few takeaways from her presentation:

One key advantage of growing native plants from seeds, rather than from cuttings or divisions, is that seed propagation yields more genetic diversity. This allows plant species to adapt more effectively to changing environmental conditions, an important consideration as climate change progresses.

The best time to sow native plant seeds in our area is in the fall because this mimics natural conditions and the seeds’ natural lifespan. Some seeds that are not dormant and need warmer soil to germinate can be sown in the spring; however, a simple method is to sow seeds in the fall and allow them to germinate when conditions are right. (There are a few exceptions, such as goldenrod and asters, which don’t tolerate wet or cold weather.)

There are three ways to grow native plants from seeds: broadcast them in a prepared, weed-free planting area; sow them in trays or pots and expose them to winter conditions outdoors (cover with netting to avoid predation) or in an unheated greenhouse (hand watering will be needed); and/or apply artificial cold/moist stratification by germinating seeds in a refrigerator.

A lightweight, soilless medium, such as a seed starter mix, is best for germinating seeds. Multiple seeds can be sown in trays or pots, but seeds growing close together are more prone to rot. Most native plant seeds only need a light covering of soil; in fact, planting seeds too deeply and overwatering are the two primary causes of low germination.

Seed trays or pots can be placed in the refrigerator until sprouting occurs, or seeds can be placed between layers of moist paper towels and stored in Ziploc bags. Seeds will germinate at different times (30 days to 120 days or more), depending on their stratification requirements.

Once the seeds have germinated, the seedlings will need to be pricked out and transplanted into containers with more nutrient-rich soil. The sprout-end should be planted into the soil so the seedling is able to develop its root system.

Some native plants that bloom in summer or fall can be planted out in the spring; however, many native plants should be planted outdoors the following fall when their root systems are more developed and they have a better chance of surviving summer drought. Patience is required as it takes three to five years for many native plants to bloom. Once they do, however, seeds can be harvested and the process can be repeated to add more native plants to your garden or to share them with other gardeners.

Learn more about growing native plants from seeds from Master Gardener Lynn Kunstman as she presents “Stratifying Native Seeds” from 10 a.m. to noon on Saturday, Nov. 18, at the Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center, 569 Hanley Road, Central Point. Registration cost is $10 or $15 at the door. Register at https://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/jackson/events/stratifying-native-seeds.