Rogue Valley road officials detail strain as budget shortfall looms

Published 5:00 pm Monday, August 12, 2024

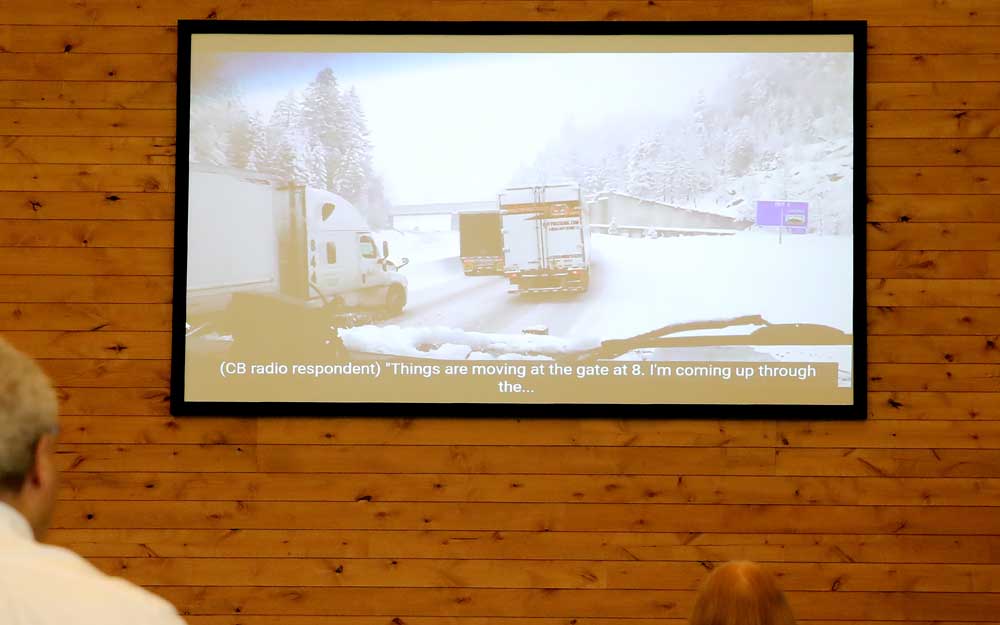

- Ahead of a tour across the Rogue Valley's roadways, ODOT Regional Director Jeremiah Griffin shows state legislators a video about the importance of "pusher trucks" at the Siskiyou Pass to the California boarder.

Southern Oregon road officials last week outlined grave concerns as they urged state lawmakers to confront a growing budget shortfall.

Touching on everything from the Oregon Department of Transportation’s unique semitrailer-pushing trucks that minimize delays on Interstate 5’s tallest mountain pass to fears that staffing cutbacks will impact road crews’ ability to respond to another Almeda Fire-level evacuation, officials with ODOT, Jackson County Roads and the city of Medford shared how they were adapting to declining gas tax revenues and rising costs.

They also warned Oregon legislators on the Joint Committee on Transportation — as well as local lawmakers, including Ashland’s state Sen. Jeff Golden and state Rep. Pam Marsh — that the center won’t hold.

During a presentation and bus tour Thursday, ODOT District Manager Jeremiah Griffin, in charge of roads in Jackson, Josephine, Douglas, Coos, Curry and portions of Klamath counties, highlighted the importance of a specially weighted truck nicknamed “The Bulldog” the agency uses during the winter to push semis that find themselves stuck on the Siskiyou Pass on I-5 near the California border.

Built in 1999, the truck spares semi drivers the cost of a tow, and it helps keep roadways clear and helps drivers in some places even plows can’t get through.

“Even a tow truck can’t get there,” Griffin said, pointing to a video demonstration of The Bulldog pushing a semi. “If we don’t have that tool, it leads to significant challenges.”

Highlighting the importance of the Siskiyou Pass to north-south supply chains, Griffin said a 24-hour closure on the pass costs roughly $1.1 million. Commercial trucks make up a third of Siskiyou Pass traffic, according to ODOT, and the agency has responded to 6,485 crashes over the past three years. Each minute a lane is blocked leads to four minutes of traffic backups and compounding risks of backup crashes.

The Bulldog is one of three trucks made between 1999 and 2001 loaded with 5 tons on their rear wheels and a massive push bumper. None are in the pipeline for replacement, Griffin said.

Beyond aging equipment, ODOT interim regional manager Darrin Neavoll voiced concerns to legislators on a Rogue Valley Transportation District bus tour about the 189 employees in his region — some 63 marked to lose their jobs if proposed budget reductions aren’t addressed in the 2025 legislative session.

“They’ve known this is coming, but we actually have to turn in position numbers, and so it’s kind of hitting home this week,” Neavoll said.

It was but one example Oregon legislators were told of how declining revenues and staffing cuts are impacting local roads departments.

Cuts impacting roads at every level

As ODOT highlighted the severe cuts they face in a budget shortfall, Jackson County Roads & Parks Director Steve Lambert and Medford Public Works Director John Vial emphasized the historic 50/30/20 funding allocation in the State Highway Fund: 50% to ODOT, 30% to counties and 20% to cities.

The highway fund’s $20,290,193 to Jackson County Roads makes up 83% of the department’s revenue. Medford’s $6,941,000 made up 38% of the city’s 2024 transportation revenues, with another 46% coming from street utility fees and $2,850,000 from street service development charges.

According to numbers provided by Vial, Medford alone has 288 miles of street, 191 miles of stormwater runoff systems, 7,736 street lights and 122 traffic signals in the city of 90,887 and 27.7 square miles.

Jackson County Roads manages 758 paved miles of road using 58 staff, according to a report that Lambert compiled. Replacing that paved road is estimated to cost $600 million.

He used the report to highlight the importance of maintaining state highway funds to legislators in the face of large cost increases. Maintaining roads, even with rising costs, remains far more cost-effective than replacing them.

“Decreases in the State Highway Fund, or changes to the historic 50/30/20% SHF funding allocation between ODOT/counties/cities will cause a significant decrease in pavement condition, at a high cost to future generations when roads are in need of reconstruction,” Lambert’s report states.

Since 2017, the National Highway Construction Cost Index “has increased by over 80%” while equipment costs have risen about 25% in the past four years, according to the county report.

“I hate to lose any pavement, but we’ve got to prioritize,” Lambert told legislators. He added that it costs about $100,000 per day to pave a 1,500-foot section of Highway 99. Cost of paint has risen about 40% as part of a rise in supply chain-related costs of products containing certain chemicals.

During the bus tour, Vial emphasized Medford’s preventative maintenance strategy for pavement management using slurry seals and chip seals to extend pavement condition at the lowest possible cost during the lifecycle, especially on lesser-traveled residential roads.

Yet even with preservation, numbers show that the Pavement Condition Index has fallen roughly eight points since 2017. Between 2013 and 2017, Medford hovered around 76 on a scale where 100 is fresh pavement. As of last year, it was rated at 68.

Foothill Road: A seismic resiliency critical component

In the event of a Cascadia-level earthquake impacting the structural integrity of the Medford viaduct, Foothill Road would likely serve as a bypass.

The roadway was thus given the highest-tier priority in a seismic resiliency plan, compiled in 2023 in coordination with ODOT and local agencies, focusing on routes providing connectivity for recovery and emergency response after a major disaster, Lambert told legislators during the tour.

“So this road is tier one, the highest-tier route in our seismic resiliency plan, as an alternative north-south route for I-5 should the viaduct down through downtown Medford fail in case of an earthquake,” Lambert said.

An unfunded 2-mile section of a widening project on the north end of Foothill Road is putting completion on hiatus, Lambert told legislators during the bus tour.

“Costs for that portion of the project have risen from $4 million to $11 million,” Lambert said. “So there’s definite impact from the funding scenario to even resiliency efforts here in the Rogue Valley.”

Illegal camping concerns ‘costly’

During the tour, Griffin with ODOT highlighted significant expenses linked to transients and illegal camping between the two Medford freeway exits.

He highlighted theft of “copper and all kinds of items stolen from the signals at Exit 30 where they were out for four days,” and highlighted an effort partnering with local utility companies to protect infrastructure serving the hospitals, the airport and the Emergency Communications of Southern Oregon 911 center.

The steel fencing installed underneath the bridges to protect infrastructure near Exit 30 costs about $75,000 per side, Griffin said. He further described how 12 burning propane bottles set afire below the I-5 viaduct prompted crews to temporarily close the interstate.

“Why are we sharing this?” Griffin asked. “Well, it’s costly. It costs about $1 million for our smaller district.”

ODOT has had no dedicated litter crew for three years due to budget constraints, and the rising number of calls make it difficult for ODOT to keep up, according to Griffin.

More concerning is that with a smaller staff, they won’t be able to get to severe concerns quickly. The propane call, for instance, was one of 15 calls that came in short order.

“What scares me is we aren’t going to be able to get to it soon enough or fast enough,” Griffin said.

Will cuts impact the next Almeda-grade evacuation?

As difficult as it was for Griffin to talk to his crews about the budget and its impacts to positions, he described during a stop in front of D&S Harley-Davidson how Sept. 8, 2020, was “the worst professional day of my career.”

That day started with an early morning call asking for his assistance at the Archie Fire near Diamond Lake. He was en route, but stopped in Shady Cove to turn back to Jackson County.

“There was zero wind,” Griffin remembered, describing an “eerie feeling” that prompted him to turn around.

“I called my boss and said, ‘I’m going to Ashland because that’s typically one of the windiest parts of the valley,'” Griffin told legislators. “And by the time I got to the Phoenix area, they were toning out the fire that was in Ashland below Almeda Street.”

He called his crew manager and told him they needed someone ready to close Highway 99 and I-5.

He pulled up a photo of thick black smoke and told legislators, “This is what’s etched in my mind.”

He highlighted ODOT’s work in the first 15 days of the fire, including the 56 staff that came from all over — Coos Bay, northern Douglas County and more — helping in the post-emergency operations center, with evacuation efforts and getting people out of the way.

At one point, around 80,000 people were under some sort of evacuation notice. Vial, who at the time of the Almeda Fire worked as the county’s emergency manager, said it was the largest evacuation in Oregon history.

Griffin wondered aloud what will happen next time there is an evacuation at that level.

“We aren’t going to be able to send 56 people to help,” Griffin said. “We aren’t going to be able to do it.”