Eastern Oregon oral history project starts with ‘Paint Your Wagon’

Published 6:00 am Saturday, November 16, 2024

- About 400 cast and crew arrived in Baker City in 1968 for the filming of "Paint Your Wagon." Local residents shared memories during a special event on Nov. 12 at the Baker Heritage Museum.

Kip Carter was in the darkroom, developing film for the Democrat-Herald newspaper, when his sister called with the most unusual news.

“Lee Marvin’s in the basement shooting,” she told Kip, who was 15 in that summer of 1968.

He rushed home and found, indeed, that the movie star was practicing archery in the basement.

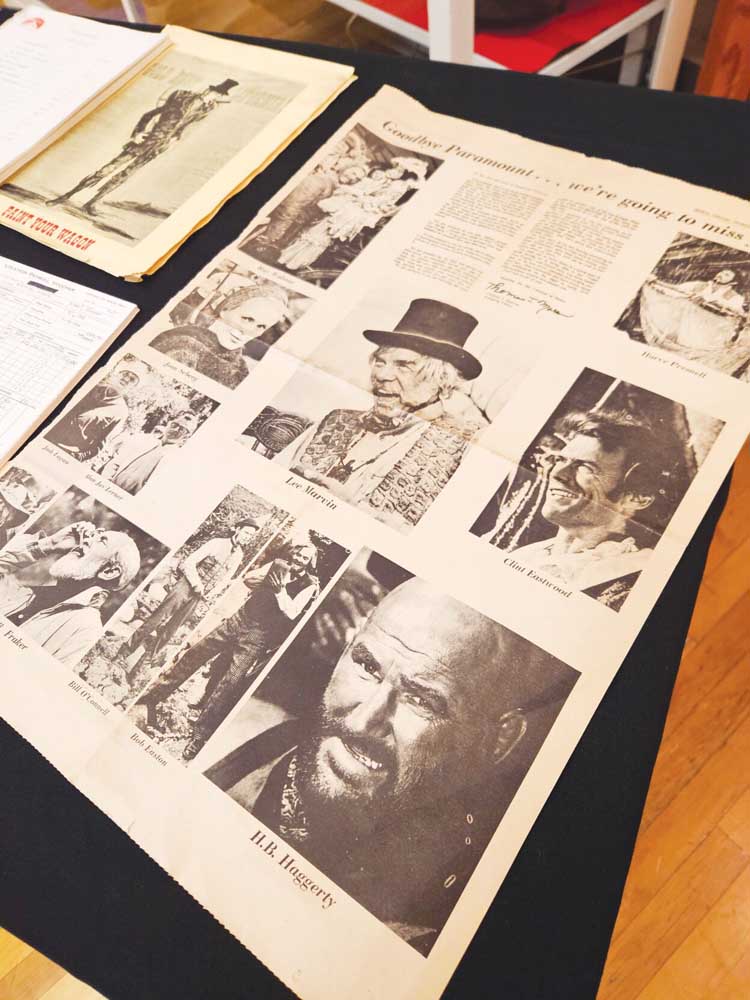

Stories about Marvin and Clint Eastwood flowed freely on Tuesday evening, Nov. 12, when residents shared memories of when, in the summer of 1968, Hollywood arrived in Baker County to film “Paint Your Wagon.”

The gathering was part of a monthly speaker series at the Baker Heritage Museum.

This one, though, was a bit unique.

Baker City is a stop on the Oregon Film Trail thanks to “Paint Your Wagon,” and on Nov. 12 Jane Ridley captured audio to preserve local memories.

This was the start of a project to collect oral histories of movies filmed in Oregon, said Ridley, who works on marketing communication and special events for the Governor’s Office of Film & TV (Oregon Film Office, for short).

“We’re starting right here tonight, in Baker City,” she said. “This is a brand new part of it.”

More than 600 movies have been filmed in Oregon, and the Oregon Film Office is dedicating signs to mark locations.

The first was placed in 2018 at Gleneden Beach State Recreation Site to honor “Sometimes a Great Notion.”

Baker County has signs dedicated to “Paint Your Wagon” at the Baker Heritage Museum, Geiser Grand Hotel, Anthony Lakes Mountain Resort and Richland.

Each sign has two parts. The top is the movie title, release year and synopsis. The bottom has “Did you know?” information.

Ridley is working with a digital librarian at the University of Oregon to collect oral stories that will be part of the Oregon Film Trail website.

“We need to preserve these stories,” she said. “The communities and people in the communities are the stars. Those are the stories I’m interested in capturing on the trail.”

Stories

Larry Morrison led the presentation on Nov. 12 by sharing his own story about “Paint Your Wagon.” He was 18, a fresh graduate of Baker High School, and got a job as a laborer with the film’s construction crew.

“If they had to dig a hole, I dug the hole,” he said with a laugh.

Workers boarded a bus every morning at the Oregon Trail Motel.

“I got in this old school bus and headed to the mountains,” he said.

Much of the movie was filmed at East Eagle Creek in the Wallowa Mountains northeast of Baker City. Morrison said there were two main areas — one for No Name City, and one for Tent City. He usually worked at one site while filming happened at the other location.

As he showed photographs, he pointed to a ponderosa pine tree. The artistic director, he said, didn’t like how the tree obscured the mountains so he sent a crew up to pluck the needles.

Throughout his talk, Morrison invited others to share stories.

Jean Johnson, whose dad, Sid, worked on building the movie set, was asked by a crew member what she did for fun on the weekends. When she said she was going to buck hay, he asked if he could try it.

When he left town after filming wrapped up, he gave her his 1953 Cadillac.

“My first car,” she said with a smile.

Tabor Clarke said his family had just moved into a house in the Wingville area, and his dad had turned down offers to rent it to visiting actors.

Until Clint Eastwood knocked on the door.

“About an hour later Dad comes in — kids, pack your bags,” Clarke said.

That wasn’t his only connection to the movie — in 1968, Clarke was 15 and worked at Farmterials. He and Bob Haynes went to the film site four times a week to grow grass.

“We had the most beautiful stand of grass and were so proud it was going to be in the movie,” he said.

Bruce Nichols was 15 that summer, and got hired with the catering service. He got to ride to the site in a helicopter for the first few weeks.

“It looked like all the rivets were going to fall out,” he said.

Carolyn Kulog had just graduated from Baker High, and she worked at Fancy Dan’s Restaurant (now the Oregon Trail Restaurant), where the crew loaded a bus every morning.

“It was an exciting place to be,” she said.

She even got a photo with Eastwood.

“I don’t think I knew who he was before that summer,” she said with a laugh.

Nearly everyone who shared a story said Baker City changed when the cast of 400 arrived.

“That was an exciting summer. Baker was buzzing,” Clarke said.

The budget for “Paint Your Wagon” was $20 million, and it earned $31.6 million at the box office.

The film was nominated for three Academy Awards in 1970 and won one for best music, score of a musical picture, for Nelson Riddle.

“This movie got terrible reviews, but has become a cult classic and we love it,” said Diana Brown, who is a member of the Baker County Museum Commission.

Baker Heritage Museum, which reopens in the spring of 2025, has a model of No Name City in the collection.

Film Trail

An interactive map of the 42 signs can be found at historicoregonfilmtrail.com.

In addition, the Oregon Film Office has partnered with an app called SetJetters, which allows a user to search for a movie and find out where it was filmed. It’s called the “Reel to Real Experience.”

Each Film Trail sign has a QR code to scan for quick access to the SetJetters app and directions to exact scene locations.

Editor’s note: The Baker City Herald published this story in 1968, the 40th anniversary of the filming of “Paint Your Wagon” in Baker County.

Kip Carter was plodding through a perfectly ordinary day right up to the point when his mom called him at work and demanded that he hurry home because Lee Marvin was in the basement, and he was firing arrows.

Carter hurried.

When he got to his Baker City home on that afternoon in the summer of 1968, Carter, then 15, rushed down the stairs.

He realized right away that his mom’s phone call was no prank.

Betty Carter had spoken the truth.

There, in the family’s basement, stood Lee Marvin.

And he was indeed brandishing a bow.

This sort of thing happened sometimes in Baker City during that strangest of summers.

You’d set out on an evening stroll, say, and you’d see, framed in the window of a passing car, that familiar face, that jaw that looked as if had been hewn from granite, and you’d remark to yourself, “There goes Clint Eastwood.”

Or you’d step out for a beer and maybe the fellow perched on the next stool was Ray Walston.

It was, of course, a tumultuous time most everywhere in America, that summer.

Just that spring, not many weeks before, assassins’ bullets had felled first Martin Luther King Jr., then Bobby Kennedy.

Our boys were dying every day in a country Americans were still figuring out how to pronounce.

(At least gas was cheap if you were lucky a quarter would buy you a gallon.)

But in Baker City, during that summer 40 years gone, the big story was not Vietnam, or Nixon, or the Democrats’ convention in Chicago.

The story was “Paint Your Wagon.”

The musical, set during the California gold rush, was filmed that summer in two principal places: East Eagle Creek in the Wallowa Mountains about 30 miles northeast of Baker City; and at Anthony Lakes in the Elkhorns about 35 miles northwest of town.

Kip Carter knew all about “Paint Your Wagon.”

So although he was bewildered as to why Lee Marvin, one of the movie’s stars, was practicing archery in the basement, Kip wasn’t exactly shocked to see the actor.

Kip was working that summer as a photographer and darkroom technician at the Democrat-Herald (these days we call ourselves the Baker City Herald).

He had already taken photos at the movie locations.

Also, Kip’s dad, Truman, an accomplished archer and the P.E. teacher at Baker Middle School, had invited actors and stuntmen to lift weights in the workout room he had set up in the BMS gymnasium.

“It was an interesting summer,” Kip, who’s now 55, said this week.

“There was a lot going on, and you would see the stars from time to time.”

Just not always in your cellar.

What happened is that Truman, having learned that Marvin was something of a bowman himself, told the actor he was welcome to come by and fling a few arrows.

Then one day Marvin did.

Kip said his sister, Tam, who was 16 that summer, later told him how she met Marvin.

Tam was washing dishes in the kitchen at the Carter home on Seventh Street, just south of Campbell.

She heard a deep voice say: “Hello there, sweetheart.”

Tam, startled by the sudden voice, looked outside. She saw Marvin walking toward the door leading to the basement.

Not long after, but before Kip came home, his uncle Bud Scott, who was visiting from Minnesota, arrived at the Carter house.

Someone told Scott to go downstairs.

“He was extremely surprised to see Lee Marvin standing right in front of him, shooting a bow, when he got to the bottom of the stairs,” Kip said.

Later, Kip took many photographs of Marvin shooting arrows both in the Carters’ basement and in a neighbor’s yard.

Before he hoisted his camera, though, Kip picked up his own bow.

He and his dad had worked up quite a routine to exhibit their shooting prowess.

Truman would toss 10-inch-diameter targets into the air, and Kip would try to pierce each with an arrow, and pin the target to the straw bale that served as a backstop.

Then they’d switch places.

“I could hit four out of six, sometimes five,” Kip said. “I was pretty good at it.”

But showing off for family and friends had hardly prepared the teenager for the more daunting task of impressing a Hollywood star.

Kip nocked an arrow, though, and waited for his dad to throw the first target.

Kip let go his arrow.

Its tip buried harmlessly in the straw bale.

The target fluttered to the basement floor.

Kip shot five more arrows.

The result was identical each time.

Kip, ashamed and embarrassed as only a 15-year-old can be who has utterly failed at some task while adults watched, collected his arrows.

“Lee Marvin said ‘hey, don’t worry about it,’ or something like that,” Kip said.

“I was just flustered. That was a lot of pressure, a major movie star watching. I was a little starstruck at that point.”

Or possibly more than a little.

Later that summer Kip drove to Anthony Lakes to take photos for the newspaper.

The movie crew was filming the stagecoach scenes on the ridge at the top of the ski runs.

Well, Kip didn’t actually drive.

“I was only 15 and I just had my learner’s permit,” he said. “It was kind of embarrassing that I had to get a ride from my mom or dad.”

The place was bustling with actors and extras, among them Kip’s dad, who had grown a beard over the preceding weeks for just that purpose.

Kip saw Walston, who played the role of Mad Jack Duncan.

Kip, who had brought an 8 mm movie camera as well as his still camera, asked Walston if he could film the actor.

“He said no, let me take some pictures of you,” Kip said.

Walston filmed Kip along with his mom and his younger sister, Holly, who was 11.

Kip never met Eastwood, “Paint Your Wagon’s” biggest star.

But his sister Tam did.

She was baby-sitting stuntman Fred Waugh’s baby while he exercised at the BMS gym.

Tam was kneeling to talk to the baby when she heard her mother say “Hi, Clint.”

She turned around and there stood Clint, talking with Waugh.

Forty years after, Kip said he doesn’t remember everything that happened that summer that had to do with “Paint Your Wagon.”

But he’s certain that no summer was like that one.

More than a year later “Paint Your Wagon” was released.

Kip watched the movie at the Eltrym.

Still today, when he sees a scene from the film or hears someone talking about it, he remembers those hot days between his ninth- and 10th-grade years.

“I felt kind of honored,” Kip said, “to be in the position just to be a part of all that.”

— Jayson Jacoby, Baker City Herald