Phoenix could have a newly named creek in town: Beaver Creek

Published 12:00 pm Thursday, March 13, 2025

Wetlands group wants state officials to recognize the small waterway, which is fed by natural springs that were located after the Almeda Fire

A Phoenix-based group that located a number of natural springs in town after the devastating 2020 Almeda Fire roared through the city is seeking to have a small stream fed by the springs named as Beaver Creek.

Save the Phoenix Wetlands has applied to the Oregon Geographic Naming Board to get the waterway officially recognized. The process would then move to the federal level for the final OK.

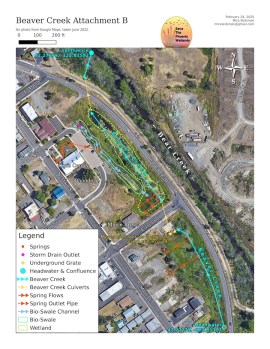

The stream, located west of Bear Creek Drive — where motorists drive along Highway 99 and enter downtown Phoenix behind Puck’s Donuts the Phoodery and the Phoenix Civic Center — is formed by six of the springs that were located after the fire.

In 2023, the organization successfully got a similar nearby stream named Blue Heron Creek.

This map shows so-called Beaver Creek with springs and their paths in orange. (Save the Phoenix Wetlands Group)

In all, 16 cold water springs have been located between Anderson Creek and Coleman Creek in what the group calls “The Miracle Mile.” The cool water provides shelter spots for salmon and steelhead in Bear Creek during hotter summer days.

“This is rather unique. They are close enough to Bear Creek to keep the temperature down,” said Robert Coffan, who spearheads the group’s efforts.

Other streams that cover longer distances would have temperature increases during the summer. The springs are only a few hundred feet or less from the creek.

The so-called Beaver Creek is located next to the berm where Bear Creek Drive runs along the Bear Creek Greenway. Three of the springs are north and three are south of 1st Street. A culvert takes the stream underneath 1st Street.

The creek lies in the former Bear Creek channel, which was moved east of Bear Creek Drive when that roadway was created in 1951. A culvert feeds the Beaver Creek water into Bear Creek at the north end. Two of the springs are located close to Moxie Brew on 1st Street. One rises by the Civic Center on Main Street, and its waters are channeled through a bioswale to the creek.

Phoenix City Council recently approved a letter from Planning Director Zac Moody supporting naming the creek adjacent to the Civic Center. Beavers lived in the stream and wetlands area created by the springs prior to the Almeda fire.

“You have something everyone calls a ditch,” said Coffan. “All of a sudden, they realize it’s a stream.”

“What we look at is fish. There could be other springs in other places, but the native fish — salmon, steelhead and trout — in the summer time, this is their thermal refuge,” said Frank Drake, a Rogue District assistant fish biologist for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Native fish show up in the Phoenix section of Bear Creek when you don’t find them in the lower sections, said Drake. From Medford to Central Point, there is little water in Bear Creek during the summer. Non-native fish do remain in that section, but the native fish will seek the cooler water upstream.

“We are very interested in the cool water that comes in around Phoenix. They allow the (native fish) to hold in Bear Creek and spring-fed tributaries,” said Drake.

A constant flow from the springs — about 45 gallons per minute — runs year-round, said Coffan. “That’s not much, but it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t have to cool all Bear Creek. The fish find their little pockets.”

Juvenile steelhead have been netted in Beaver Creek, said group member Scott English. “When we have a big rain event, that’s when they start moving,” he said.

Bill Thornhill and Scott English of Save the Phoenix Wetlands look at where a spring comes out of the ground next to the Phoenix Civic Center. The spring was previously covered up by the Dive Shop business on Main Street. It now helps cool the so-called Beaver Creek and Bear Creek. (Tony Boom)

A trail created in the last decade exists in the bioswale area and wetlands below the Civic Center. The group is encouraging development of more trails, including some that would lead from businesses down to the wetland area. Phoenix is applying for a grant from the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department that would help rehabilitate the wetlands area and create more trail features.

After the northern section of the creek is rehabilitated, the group would like to see a similar effort made in the area south of 1st Street.

Application for naming a creek is first made to the Oregon board. Its approval would then send it to the U.S. Geographical Naming Board for a final decision.

“A formal name increases public awareness of a stream,” said member Pam Thornhill during a presentation to the present council in February. It would also be included in geographic mapping systems that are used by the state and the county.

“Named streams tend to be protected and managed better than unnamed streams because they are identified in aquatic inventories and state, county and jurisdictional planning overlays,” Moody wrote in his letter.

Information needed for the naming process includes a location description, listing of features, length, width, flow rates, a map showing the head water and an explanation of the proposed name. All Save the Phoenix Wetlands members contributed to the information gathering process, Thornhill said.

The wetland group worked with Rogue Riverkeeper to put a name on the stream formed by springs near Blue Heron Park. The name became official on Oct. 12, 2023.

The wetlands group became interested in the area after a proposal for a commercial development on land owned by the city’s urban renewal agency emerged. The Almeda Fire had removed blackberries, revealing the springs’ existence.

A $238,250 grant for the removal of a rock berm that prevents water from Blue Heron Creek reaching Bear Creek has been awarded by the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Department’s Private Forest Accord program. The grant proposal was prepared by the wetlands organization, but was awarded to Rogue Basin Partners, which has nonprofit 501(c)(3) status that the wetland group lacks.

The 600-foot long rock berm was built as part of the Bear Creek Drive project that rerouted north-bound Highway 99 and moved the Bear Creek channel.

Besides working to discover, name and preserve natural springs, the wetlands group is involved in a number of other activities, including cleanup and restoration days and wetlands education. They have assisted the Rogue Valley Watershed Council and the Rogue Valley Council of Governments in monitoring water temperatures in Bear Creek.

Springs lie both north and south of the “Miracle Mile,” said English. But there hasn’t been much research done on those yet, he noted.

Tagline: Reach Ashland freelance writer Tony Boom at tboomwriter@gmail.com.