Oregon bill would reduce administrative burden for patients seeking physician-assisted suicide

Published 8:45 am Tuesday, June 3, 2025

Senate Bill 1003 proposes to amend Oregon ‘Death by Dignity Act’

Terminally ill people who want their doctors’ help in dying could do so twice as quickly under an Oregon bill that would cut the waiting period between asking for a lethal dose of medication from 15 days to seven.

Oregon is one of 11 states and Washington, D.C., that allow terminally ill individuals to choose to end their lives by asking a physician for a lethal dose of medication. Only adults who are given six months to live and who can effectively communicate for themselves can elect for physician-assisted suicide. In 2023, the state removed a residency requirement, enabling people from other states to travel to Oregon to die.

Patients must make two oral requests to their physician for the medication, each separated by at least 15 days. But Senate Bill 1003, as amended, would change the law and reduce that time frame from 15 days to seven days.

Trending

The bill would allow electronic transmission of prescriptions and filings, and it would require hospices and health care facilities disclose their physician-assisted suicide policy before a patient is admitted and publish the policy on their websites. The bill would also broaden who can prescribe lethal drugs by replacing “attending physician” and “consulting physician” in the law with “attending practitioner” and “consulting practitioner” while retaining the requirement that they are licensed physicians in Oregon. The bill is sponsored by the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The bill received a public hearing Monday afternoon in the Senate Committee on Rules, with dozens of individuals testifying and submitting letters mostly in opposition. It has yet to receive a vote by either chamber.

Oregon ‘Death by Dignity Act’ bill changes sparks significant opposition

The state’s policy, called the “Death by Dignity Act,” was created through a 1994 citizens initiative that passed with 51% of the vote. A lawsuit paused the act from taking effect for three years, but in 1997 that injunction was lifted and an attempt to repeal the act in a citizens initiative failed the same year.

In 2024, 607 people received prescriptions for lethal doses of medications, according to the Oregon Health Authority. Most patients receiving medications were 65 or older and white. The most common diagnosis was cancer, followed by neurological disease and heart disease.

Most individuals, including mental health providers and Christian medical groups, testified in opposition to the bill, saying it would undermine the time needed for patients to process their diagnosis, disregard alternative health solutions and ignore mental health concerns. The committee received 429 letters in opposition to the bill and only 12 letters in support.

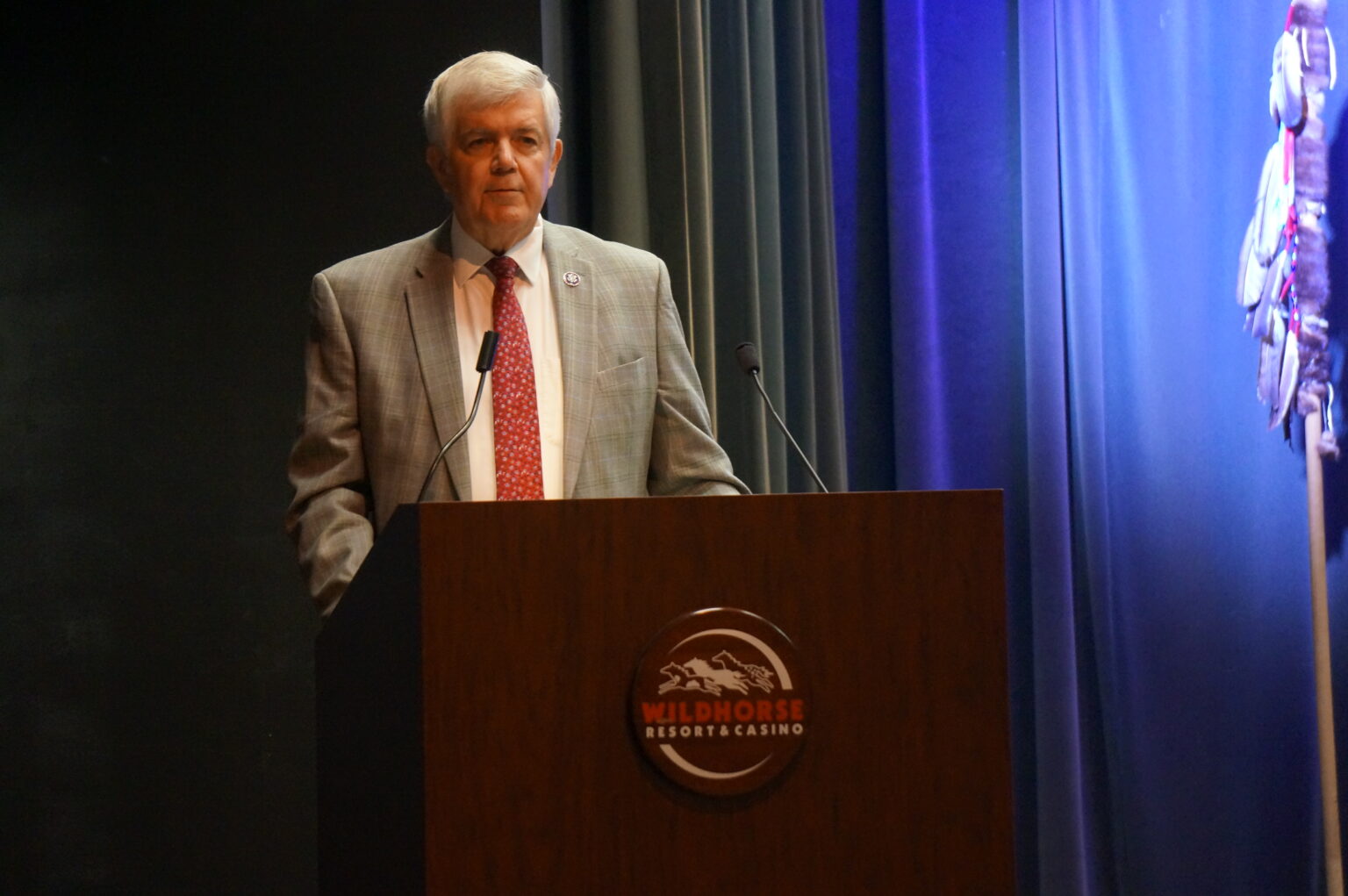

Rep. E. Werner Reschke, R-Malin, said it “creates a culture of death over that of life.”

Trending

But a few proponents, such as Portland resident Thomas Ngo, said it would make the process smoother and less of an administrative burden for patients enduring terminal illness and pain.

Ngo said his mother used the Death with Dignity Act to die after she was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

“Her passing was peaceful and on her teams,” Ngo told the committee.

Ngo’s father’s partner died of the same disease but could not opt for physician-assisted suicide because they were at a religiously-affiliated health care provider. Oregon health care providers are not obligated to participate in the Death by Dignity Act, and many religiously affiliated hospitals do not participate.

The bill will be scheduled for a work session for a later date where the committee can decide to hold the bill — killing it for the remainder of the session — or advance the bill to the Senate floor for a vote.