Crying in the Oregon Legislature: Lawmakers keep breaking into tears, unheard of a generation ago

Published 10:05 am Monday, June 16, 2025

- Clockwise from upper left are Rep. Annessa Hartman, a Gladstone Democrat; Sen. Janeen Sollman, a Hillsboro Democrat; Rep. Hai Pham, a Hillsboro Democrat; Rep. Kevin Mannix, a Salem Republican; Rep. Dacia Grayber, a Portland Democrat; and Rep. Darcey Edwards, a Banks Republican.(Credit: Screenshots from Oregon Legislative Information System)

In her three years in the Oregon Legislature, Rep. Annessa Hartman says she has cried in front of colleagues so many times that it no longer vexes her.

The Clackamas County Democrat says it’s impossible to separate the emotions that come with the trauma of her past — sexual assault and domestic violence abuse — from the bills she champions on behalf of victims.

“I didn’t step into this space thinking ‘I’m going to cry all the time,’” said Hartman, of Gladstone. “I’m 37. I’m still coming out of a generation where women shouldn’t cry, especially in male-dominated spaces … and that being emotional is a weakness.”

But Hartman along with a cadre of her colleagues — male and female, Democrat and Republican — have bucked those social mores, saying their difficult life experiences actually make them better legislators.

Perhaps more than ever this session, they have been sharing personal stories of distress as they advocate for bills that touch the very fabric of who they are. And sometimes, that has come with tears. In public hearings. On the chamber floors. And with legislative cameras rolling — livestreaming the details for all the internet to see.

Rep. Dacia Grayber, a Democrat from Southwest Portland, spoke of her adult stepdaughter who died by suicide while voicing her support for a measure recognizing Youth Suicide Awareness Day.

Rep. Darcey Edwards, a Republican from Banks, advocated for a system that would allow homeless youth to easily “call your mom,” as she has talked about the heartache of searching for her own son, who was drug addicted and homeless on the streets of Portland.

Rep. Cyrus Javadi, a Republican from Tillamook, pushed for victims’ rights when he divulged to a chamber full of 50 colleagues last month that he’d been sexually abused by a babysitter when he was a child.

Rep. Shelly Boshart Davis, a Republican from the Albany area, jokes that she has become the “face of menopause” after she shared her private ordeal with perimenopause and urged colleagues to remove roadblocks to hormonal care.

Others in the past few years also have shared stories of a daughter’s abortion, fleeing an abusive father as a child with their worldly possessions in a garbage bag, flunking out of college and getting arrested four times.

Long-timers in the Legislature say such unfiltered openness was unheard of a few decades ago, when sharing personal stories that could cast shame upon their tellers — however unwarranted — almost never happened. Back then, they say, virtually the only tears shed were in joy over the passage of hard-wrought legislation or in grief while eulogizing the deceased.

But many legislators agree that something new and more widespread is underway — even if not everyone embraces it.

An extraordinary shift

Theories abound. Is it that society is simply more accepting of the trauma so many people have endured and that social stigmas are beginning to fade? Or a wave of newer legislators with fresh ideas about what’s socially acceptable? Or that, encouraged by TikTok, YouTube and podcasts, fewer secrets remain in the dark as so many people share intimate details of their lives?

Some lawmakers ponder if the much wider inclusion of women — who now make up 46% of the Legislature — has contributed to an atmosphere of openness and tears. Others, however, resent that stereotype, noting that there are plenty of men who’ve been unguarded, too.

Some also wonder if the Oregon Legislature is mirroring a national political trend. Members of Congress have shared stories about rape or abortion that helped inspire more support for women’s rights. Washington state Rep. Debra Lekanoff has called for better access to addiction treatment after announcing in 2024 that she was just a few months into recovery for substance abuse.

Some pundits and lawmakers themselves say there’s a fine line between being real and going too far. Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman, who was forthcoming in the 2022 election about struggles with depression, now says he believes his frankness has been weaponized against him. Former U.S. Speaker John Boehner famously became the butt of jokes when some believed his tears came a bit too often.

The Oregonian/OregonLive reached out to a dozen Oregon senators and representatives who all had shared personal stories, most ending up in tears.

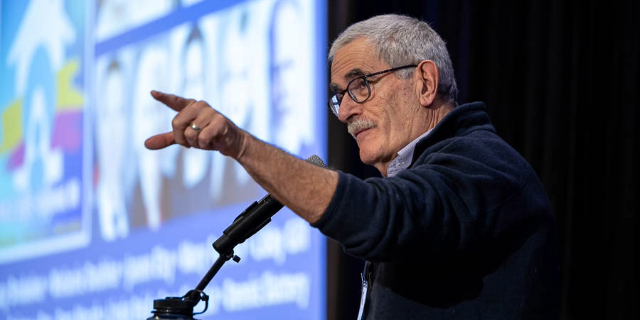

Rep. Hai Pham, a Hillsboro Democrat, said just before taking office in 2023 he visited Salem and noticed the emerging trend.

“I thought, ‘Why are these people crying on the House floor?’” Pham said. “‘Why are they showing all that emotion?’ I thought, ‘I’m not going to be that guy.’ And then when you get down here, you hear all these stories of people hurting and reaching out to you, and you try to help them, and they get to you.”

Now into his third legislative session, Pham says he’s cried four times. That includes while speaking in support of a measure to commemorate 50 years since the end of the Vietnam War and while pushing for the passage of a bill that requires insurance companies to expand coverage of hearing aids.

Pham is a Vietnamese immigrant whose mom was pregnant with him when she and his dad escaped communism on a boat. He also is the dad to two children, ages 1 and 3, and said his “dad hormones” surged when he learned through testimony before his committee about a father who couldn’t hear his daughter call him “Dad” because the man couldn’t afford to replace his broken hearing aids.

The tears, Pham said, are driven by compassion and the drive to do more.

“Back in the old days, people would say that’s a vulnerability,” added Pham, 46. “But I think now it’s superhero strength.”

Hartman, the Gladstone representative, said she, too, hadn’t anticipated crying on the job when she took office in 2023.

She has shared snippets of her past — saying that she was sexually assaulted when she was 18 or 19 in the walk-in cooler of a restaurant and later endured domestic violence from a past boyfriend while she was still a young adult. She said she knew that, once elected, she would push for victim-centered legislation.

But the first time the tears flowed during a public hearing came as a surprise, Hartman said.

“I was like ‘Oh God, I can’t believe I cried,’” she said.

However, after receiving an outpouring of stories and support from other survivors, she decided she wouldn’t let up — even if that came with tears.

“I’m going to take my pain and my story along with all of their stories and channel it into this work,” Hartman said.

Hartman said her two daughters have helped her realize she shouldn’t be ashamed of the emotions that still surface today because of her past. Something her younger daughter said to her early on, in particular, stuck with her.

“My then-9-year-old said, ‘Think of your tears as power tears,’” Hartman recalled.

Moving past stigma

But not everyone sees it that way.

Hartman said twice other lawmakers, both women with more years in the Legislature, have offered well-intentioned advice.

“I’ve been faced with comments like, ‘You are being too vulnerable. You are being too emotional. You should tone it back a bit,’” Hartman said.

Sen. Janeen Sollman, a Hillsboro Democrat, said she also has received that advice after one of the “many times” her raw emotions have risen to the surface.

“I remember one legislator, they told me later, ‘Oh, you’ll never see me cry on the floor because I think it shows weakness,’” Sollman said. “And I said, ‘I don’t see it the same way.’”

One of Sollman’s impassioned moments came when she advocated for a 2023 bill that would ensure that child welfare officials have a supply of duffel bags at the ready in case they have to hastily move foster children out of dangerous living situations. Sollman recalled her own story: When she was young, she guesses no older than 10, she, her mother and her older sister packed up and left her abusive father so quickly that she had to stash her possessions in a plastic garbage bag. When the trio arrived at the Dunes Motel in Hillsboro, the front desk clerk looked down at her as he asked what was in the bag, thinking she was planning on bringing trash into her motel room.

She remembers how awful that felt.

As tears filled her eyes, Sollman told colleagues she never wants foster children to feel humiliated like she did.

Sollman, now in her 50s, said she draws on her personal history, just as others around her have drawn on theirs.

“I just feel that that’s the beauty of a citizen Legislature,” Sollman said. “That we all come to this with different backgrounds, different experiences. … That can lead to better legislation. And sometimes that process gets emotional.”

‘People do their best to hide it’

Like many of his colleagues, Rep. Rob Nosse, a Southeast Portland Democrat, can recall every instance that he’s cried on the job. A legislator of 11 years, Nosse has let his emotions well to the surface going farther back in time than most. They come easily to his mind, like the time he spoke about a change in the law that allowed him to marry his husband. Or when he stood in support of abortion rights, sharing that his daughter had had an abortion, too.

“I always think the Legislature has been an emotional place, it’s just that people do their best to hide it,” Nosse said.

He believes sharing difficult personal stories, with or without tears, makes lawmakers more relatable.

Nosse recalls then-Rep. Dan Rayfield’s speech after Rayfield was voted speaker of the House in 2022. In it, the Democrat who is now Oregon’s attorney general, unveiled many traumatic and unglamorous details of his life: Growing up with a mother battling addiction, tagging along with her to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings as a child, enduring physical abuse by a stepparent, graduating late from high school because he’d skipped so many classes, flunking out of college with a 1.4 GPA and getting arrested four times as a teenager for driving while intoxicated and other misdemeanor crimes. Rayfield, then a successful lawyer and state representative of nearly 10 years, explained to his colleagues on the House floor that he was spilling these details to show he was “living proof that the worst moment of our lives doesn’t have to be our destiny.”

Nosse said Rayfield’s candor changed his view of him.

“Dan Rayfield, when I first served with him, could come off like a hotshot lawyer, pretty boy, know-it-all,” Nosse said. “I couldn’t stand that guy my first couple terms.”

But after Rayfield spoke so openly, “I was like ‘Ohhh. Look at you,’” Nosse said. “It made me like him a lot better. And it made me understand certain things about him.”

‘So many trolls out there’

It was during a discussion this session on the House floor about whether to allow sex abuse victims unlimited time to file lawsuits that Javadi, the Tillamook representative, decided to share his story of abuse by a babysitter. He was a 12-year-old child. His mother was working three jobs. Now 48, he said he’d told “maybe two people” in the 36 years since.

One was his wife, who was sitting next to him that late May afternoon. He said he asked her if she’d be ashamed if he told colleagues what happened to him and why he stayed silent for so long. She encouraged him to do what he felt was right.

Javadi spoke with gravitas but didn’t weep. Even so, he said he worried people might look at him differently upon revealing he was a male who’d been victimized.

“There are so many trolls out there and people say a lot of mean, negative things,” said Javadi, who added that as it turned out, he only heard words of support.

Javadi said his disclosure had nothing to do with political gain.

“Sometimes we are so worried about the next campaign or how it will look,” Javadi said. “That ends up turning us into a version of who we are that’s not very authentic. And if we expect the public to trust us, then we need for them to see the full picture, not just that polished version.”

It was during that same floor discussion that Rep. Kevin Mannix, a Republican from Salem who first was elected to the Legislature in 1989 and then returned in 2023 after a long break, found himself awash in emotion in front of his colleagues for the first time.

“I became choked up thinking about all the victims whose lives and stories would be different if we had been more aggressive about dealing with sexual exploitation and assaults,” Mannix said. “Somehow, it just flowed over me as I was talking.”

Mannix, 75, said he doesn’t think less of the others he has seen cry. Though legislative rules forbid expressing certain emotions — like anger that manifests in shouting — he notes “we don’t have a rule against tears.”

And was he — a lawyer, former gubernatorial candidate and long-time legislator — embarrassed by his tears? No, said Mannix, like so many others.

“Not at this stage,” Mannix said. “Maybe 25 years ago.”