THE DEATH OF BOBBIE KOLADA, Part 5: ‘I don’t want her to have died in vain’

Published 5:42 am Thursday, May 25, 2023

- Scan 5 Caregiver

EDITOR’S NOTE: Final of a five-part series.

******

In the two months since 66-year-old caregiver Bobbie Kolada died of injuries suffered on the job, little has changed at the group home in east Medford where she was hurt.

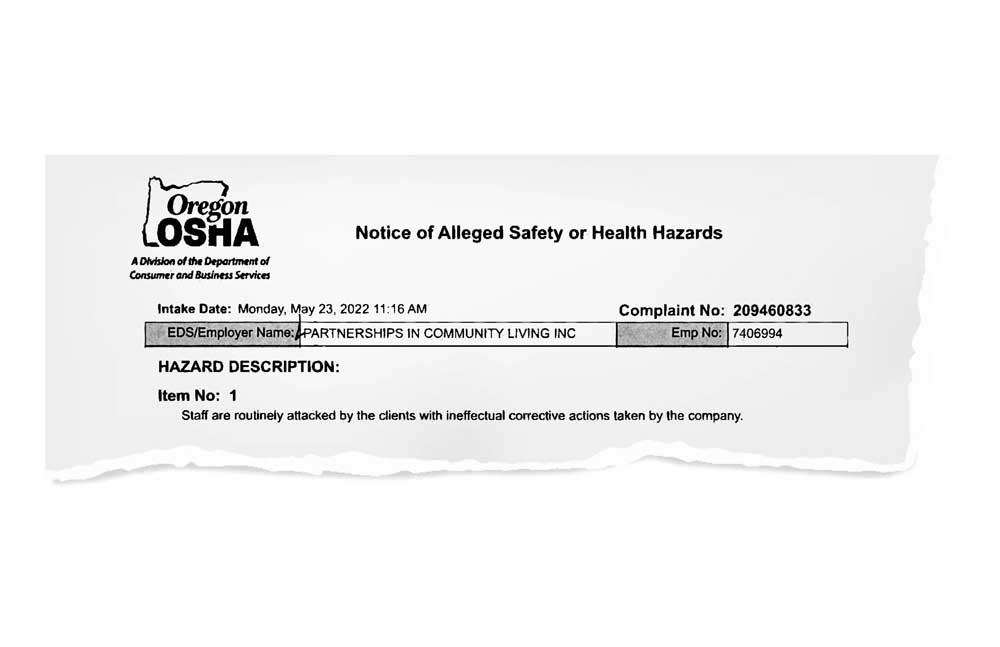

The developmentally disabled man accused of sending her to intensive care still lives there. Kolada’s co-workers continue to provide for the man’s care. And the same is true of other residents who have hurt other caregivers at group homes operated by Partnerships in Community Living, current and former employees say.

Kolada was injured Feb. 20. Working alone and caring for two residents at a PCL group home, the 5-foot-4 grandmother sustained crushed cervical vertebrae and a massive head injury, which led to her death five weeks later at Asante Rogue Regional Medical Center. The cause of death listed on her death certificate was a subdural bleed, a head trauma resulting in a brain bleed that compresses brain tissue.

The resident who apparently injured Kolada has hurt at least one other caregiver since that night. The resident had injured Kolada and others previously, according to Kolada’s co-workers, who say drastic changes are needed to protect employees from aggressive and violent residents housed by PCL.

Group homes like those operated by PCL provide care for people with severe developmental and intellectual disabilities whose families cannot care for them.

Unable to aid in their own defense

Throughout the early 1900s, many in Oregon with intellectual disabilities lived in institutions such as the Fairview Training Center in Salem, established in 1907 as the State Institution for the Feeble-Minded.

Most of the first patients at Fairview were transferred from the Oregon State Hospital for the Insane. Fairview residents were referred to as “inmates,” and for decades just about anyone leaving the institution faced compulsory sterilization before returning to the community, according to a history of Fairview produced in 2020 by Oregon Public Broadcasting.

By the 1980s, Fairview was overcrowded and poorly staffed. In 1985, a U.S. Justice Department investigation determined Fairview residents faced life-threatening conditions. Following a federal civil rights lawsuit, Fairview closed in 2000, with most remaining residents moving into the community, including group homes like those operated by PCL.

While residential settings work well for a majority of developmentally disabled people, caregivers and others who work in the mental health field say more needs to be done to protect employees from residents with violent tendencies, who often face no consequences for their behavior.

Jackson County District Attorney Beth Heckert said that people with severe developmental disabilities are often unable to aid in their own defense, making it difficult to press charges for violent acts that otherwise would be prosecuted as a crime.

In Kolada’s case, police who responded to the 911 call were told Kolada had fallen, and no police report was filed. Medford police have since opened an investigation. Heckert said crimes such as violence against caregivers are handled differently when committed by a developmentally disabled person, but they must be addressed regardless.

“For low-level crimes, we might get a guardian who can place them someplace or do something so we can feel like, ‘OK, somebody in the community is kind of watching over this situation where we can’t really leave them out in the community unsupervised,” Heckert said.

“There would be a separate process for dealing with a dangerous offender. If somebody committed a really serious crime but could never aid and assist (in their own defense), you can commit them to the state hospital as a dangerous offender. … State statute says if they can’t aid and assist, the court has to dismiss the case, but you could civilly commit somebody … saying they’re dangerous out in the community, to themselves and others.”

If no criminal charges are filed, residents who are a threat to themselves or others are typically dealt with through a housing change.

Stabilization and Crisis Unit

Group home residents with violent tendencies can be sent for assessment and care to a state Stabilization and Crisis Unit. Some 20 group homes between Eugene and Portland operate as SACU homes, where roughly 600 employees provide 24-hour care for up to 95 people. The SACU homes are deemed a higher level of care than regular group homes, focused on stabilizing the behavior of violent or distraught residents through drugs or other treatments, so they can be returned to a regular group home.

Individuals sent to SACU typically have intellectual and developmental disabilities, combined with co-occurring mental health issues, and caring for them is a difficult and potentially dangerous job. Employees in the unit report burnout from overwork and high staff shortages, according to a March 7 story by Oregon Capital Chronicle.

Some 301 staff worked 5,020 hours of mandatory overtime at SACU in July 2022, an average of about 16 hours per employee. Some 565 staff worked 19,471 hours of voluntary overtime the same month, with employees averaging 17- to nearly 24-hour days. In terms of injuries last year, 24 employees missed nearly 2,011 hours of work — 84 hours on average per employee — due to injuries suffered on the job.

No SACU homes exist in Southern Oregon, and those in the northern part of the state have long waiting lists. Oregon State Hospital is also short of beds.

Tom Mayhall Rastrelli, spokesperson for the Oregon Office of Developmental Disabilities Services, said in mid-May that 11 individuals were waiting for SACU beds to open up. When a bed is not available, residents remain in their current placement or must find temporary housing. In some cases, a resident could be housed in a hospital behavioral unit, in particular if they have been charged with a crime or created an unsafe situation for themselves or others.

Former Oregon State Hospital spokeswoman Aria Seligmann, in a November 2021 story by Oregon Public Broadcasting, acknowledged the hospital received more patient referrals than it has capacity to treat.

“Many of the people referred do not need extended hospital level of care but remain at the hospital longer than needed because their home counties lack sufficient treatment options,” Seligmann wrote. “The Oregon State Hospital cannot build and staff enough beds to solve the problem. The solution is for our partners to work together to expand beds and treatment services in the community and preserve the state’s limited hospital capacity for people who need hospital-level care.”

Ultimately the responsibility for group home residents falls on the shoulders of county case managers, said Rastrelli, adding that state officials, case managers and providers “work hard to be proactive in situations where an individual hurts other people who live with them or the employees who work with them.”

“People who experience disabilities are treated like anyone else if they hurt other people. If it’s a mental health crisis, they go to the hospital for evaluation. They may end up in the hospital or at the Oregon State Hospital on a temporary stay. If they have committed a crime, they may be prosecuted like anyone else. Having a disability doesn’t change these situations,” Rastrelli said.

“There are people in our communities that do not have disabilities that are a danger to themselves or others. The difference is that Oregon has a number of supports in place for people with (intellectual and developmental disabilities).”

Rastrelli said placement in any type of setting is voluntary, and residents have the right to refuse services, meaning, “They might end up living with family or other people they know. They could end up houseless.”

An administrator of a Medford agency that deals with developmental disabilities, who asked that his name not be used, said PCL was “like the Fairview of Southern Oregon,” priding itself on taking the most difficult residents.

“Anybody who has been in this field for long enough knows about PCL and the kind of individuals they take on,” the administrator said.

A secure, long-term residential option for dangerous residents is sorely needed, he said.

“There are DD facilities and there are mental health facilities, but not too many places that do both. DD patients who have co-occurring mental disorders go to DD facilities, but there’s no facilities that deal with the super-violent ones.”

‘A job shouldn’t … risk your life’

Kim Demar, a former supervisor for PCL who managed the house where Kolada was hurt, said it was “a huge mistake on PCL’s part not to honor and protect their staff.” The company told employees that Kolada had fainted or fallen, and did not acknowledge the apparent attack that led to her death, Demar said. Companies like PCL have a responsibility to protect both residents and caregivers, she added.

“We don’t want to see overly institutionalized individuals, but there are some who need that level of institutionalized care, because they are extremely violent. I don’t remember signing up for the fact that I wanted to be beat up on a regular basis, or that I had to fear for my life going to work,” Demar said.

“What I really would like to see is legislation that says we’ve got to do a better job of protecting our employees. Yes, I understand these individuals are intellectually and behaviorally challenged, but that doesn’t give them the right to hurt us either. … I don’t think there’s a simple answer, but the lack of accountability for (Bobbie Kolada) and what happened to her is really why all of us are so terribly distraught.”

Kolada’s longtime roommate and former PCL employee Mechelle Leffingwell described the scene at the group home where Kolada was hurt as a house of horrors the night of Feb. 20. Kolada had asked her to go to the house to retrieve her purse. Leffingwell said she saw “blood everywhere” and remembers thinking, “A job shouldn’t be like this, it shouldn’t risk your life.”

Leffingwell, who worked at PCL from 2016 to 2021, said she witnessed frequent employee injuries, including a time when Kolada, who was working alone with four residents, was beat to the point her face was “swollen purple and black, top to bottom.”

“One of the clients, the one who actually killed Bobbie, he was big for me, and I’m 5-11. When they brought us down, in that house, from two staff to one staff, we asked if we could keep it at two, and they said no, they’re fine. One is fine.”

‘I want my mom to have a voice’

Jessica Bandy, Kolada’s daughter, wonders whether her mom could have survived her injuries if help had arrived sooner. Kolada was alone for as long as two-and-a-half hours after being injured, before the next shift arrived and called 911. Lack of acknowledgement of her mother’s injuries by PCL has been upsetting, but she takes solace in former and current PCL employees speaking out to share their own stories and report concerns to state agencies.

“There are a lot of people quietly fighting for my mom,” she said through tears.

“To know that they really cared for my mom means the world to me.”

Bandy said she didn’t fault the resident who apparently injured her mother, but felt both residents and employees of care facilities need more protections.

“I don’t want anyone else to go through what we’ve gone through. My mom had survived a lot in her life, and for it to end like this feels really wrong. She gave so much to others, and she literally died caring for others,” Bandy said.

“I don’t want her to have died in vain. I want to know what policies they’re changing as a result of this happening. I want her friends to be safe. … I want my mom to have a voice.”

Part 1: ‘Did somebody do this to her?’

Part 2: Who is investigating Bobbie Kolada’s death?

Part 3: ‘I remember thinking I was going to die’

Part 4: ‘Culture of disregard for employees’

Part 5: ‘I don’t want her to have died in vain’

Study shows nearly all caregivers suffered injuries

In a 2014 study titled “Resident Aggression Toward Staff at a Center for the Developmentally Disabled,” published in Workplace Health & Safety, an interview of 21 direct-care workers and three nursing staff revealed all had been previously injured by residents.

Twenty (83%) reported being injured while engaged in the physical restraint of a resident. Twelve (50%) reported seeing health care providers for their injuries, and 11 (46%) said they requested time off work due to injuries.

When asked about factors that contributed to injuries from resident aggression, 10 staff (42%) reported that inadequate staff had responded to the event; 20 staff (83%) reported that managers lacked concern about their safety and would not respond to their suggestions about how to handle resident aggression.

Of staff interviewed, 20 (83%) reported working overtime on a regular basis, including 12 (50%) who reported working mandatory overtime. Additionally, 13 (54%) of the staff interviewed reported that they were not fully included in the residents’ care and treatment plans, including providing input to the health care provider about behavior that might warrant medication changes. Staff also reported that changes in medication seemed to result in resident aggression.

Twelve (50%) of the staff expressed a need for more comprehensive training on handling resident aggression.

‘Justice for Bobbie’ vigil planned

Co-workers and friends of Bobbie Kolada plan to hold a “Justice for Bobbie” candlelight vigil at 7 p.m. Sunday, May 28.

Jacksonville resident Valina Rivera-Schaefer, who is helping to organize the event, is a former PCL employee who said she sustained serious injuries, including a miscarriage, while working as a caregiver for the company.

Rivera-Schaefer said she hoped the event would offer a chance for anyone who cared about Kolada — or who shared similar experiences while working in the caregiving industry — to honor one of their own.

“We want to bring awareness to the industry — that we need more safety precautions in place to protect caregivers. We’re hearing a lot of people are being told to hush about what happened to Bobbie, and it’s not right,” she said.

“We’re hoping there is a response when it comes to what caregivers are going through. We want the event to be healing and to be peaceful.”

The vigil will be held at the Asante Workers Health parking lot, 2596 E. Barnett Road in Medford, and will include a walk through the neighborhood where Kolada was fatally injured Feb. 20.