Republicans block attempt to prevent federal overreach with Oregon’s National Guard

Published 3:06 pm Monday, June 30, 2025

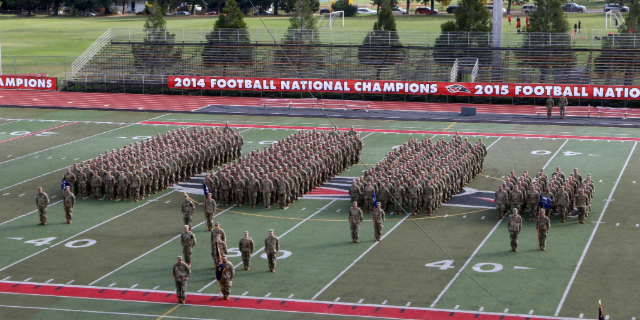

- Oregon Army National Guard Soldiers assigned to the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry Regiment stand in formation as their mobilization ceremony begins Oct. 20, 2024, on the campus of Southern Oregon University in Ashland. The soldiers were headed to the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. Courtesy photo

A bill intended to clarify when the federal government can deploy the Oregon National Guard never made it to a final vote before lawmakers went home for the summer.

Republican Senators killed the bill with a procedural move, tying it up in red tape for so long that lawmakers ran out of time to consider it before they opted to end the 2025 Legislative session Friday night, chafing chief sponsor and veteran Rep. Paul Evans, a Monmouth Democrat.

In an interview after the bill died last week, Evans said he’d tried to craft the policy to avoid party politics and criticized Republicans Cedric Hayden of Fall Creek and Daniel Bonham of The Dalles for blocking a final vote on the bill “out of partisan reasons, with no respect whatsoever for history.”

“I can’t ever forgive them,” Evans said. “I can’t see them as anything less than people that care more about their political situation than they do what’s right.”

Asked for a response, Hayden praised Evans for his decades of military service and “continued commitment to our military,” but he said he’d rather see the state expand benefits for National Guard members than intervene in government arm-wrestling. Bonham argued his party shut down a political attack.

The bill was “never about deployment standards,” Bonham said in an email. “It was a political statement aimed squarely at Donald Trump. We saw right through it and acted accordingly.”

House Bill 3954 sought to draw clear lines on when the federal government can call upon Oregon’s National Guard, an attempt to prevent President Donald Trump or future presidents from ordering state troops to act as law enforcement. Supporters of the bill wanted to make clear that U.S. presidential administrations don’t have the power in Oregon to do what the Trump administration did in Los Angeles earlier this month: deploy California’s National Guard to respond to protests against the will of the state’s governor. Trump said he has the power to use the troops when local law enforcement “can’t get the job done.”

Military troops are not trained to enforce the law, Evans said, and have a lower threshold for using lethal force than police officers do.

At stake, Evans argued, is a repeat of Kent State – the 1970 slaying of four university students by the Ohio National Guard during a protest against the Vietnam War. He doesn’t want to see young Oregon National Guard troops put in that position.

“It is bad enough to execute policy in a manner that takes life,” Evans said. “But putting kids in that environment, against their own neighbors and their own communities, because you’re trying to prove that you’re somehow tough on immigration – it’s unacceptable.”

Evans’ bill detailed when the federal government could call upon Oregon’s National Guard and specified that the troops can’t be used for law enforcement or immigration enforcement. The bill also would have required Oregon’s guard-leading adjutant general to override even otherwise acceptable federal deployments if Oregon’s troops are needed for an in-state emergency like a wildfire.

The bill passed out of the House on a party-line vote in late June, then went to the Senate Rules Committee. Democrats approved advancing the bill to the House, but Bonham and Hayden voted against doing so. The Republicans said they wanted to file an alternative bill through a minority report, a procedural move that delayed the bill’s potential vote on the Senate floor beyond the constitutional June 29 deadline to end the legislative session, Evans said.

Hayden argued lawmakers should replace the bill with a measure to expand dental health and free college benefits to National Guard members instead of getting in a “legal match between federal and state governments.”

“If the state is going to dictate policy as it relates to the National Guard, we should be dictating policy that supports guard members and their families,” Hayden wrote in an email.

Oregon’s National Guard is struggling with enlistment, Evans said, and should the federal government call on state troops, Kotek may not have the people she needs for in-state emergencies. He’s encouraged her to keep the guard busy to underscore that point. Oregon’s troops could be a huge help providing judicial security in understaffed courthouses or helping with prison logistics while correction workers are stretched thin, Evans said. They will likely also need to help Oregon’s firefighters as a bad 2025 fire season races to an early start.

In the absence of the bill, Evans said, he’s also encouraging Kotek to draft an executive order outlining appropriate use of the National Guard and triggers for when she might veto attempts to mobilize them.